The European Union is committed to reducing fluorinated greenhouse gases (F-gases), as part of its broader climate action efforts. These gases, including hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), have significant global warming potential and their reduction is essential to meeting climate targets. Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) represent around 90% of all F-gases, and their worldwide reduction is essential to meeting global climate targets. The EU has been working closely with its global partners to phase down HFCs, under international agreements, most notably through the Montreal Protocol.

The success story of the Montreal Protocol

The Montreal Protocol stands as a remarkable success story in the fight against environmental degradation. Substances like chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), once commonly used in refrigerants, as well as solvents, aerosol propellants, and foam-blowing agents, were discovered to significantly harm the ozone layer.

In response to this, the international community united in 1987 under the Montreal Protocol to phase out the production and use of these harmful substances. This decisive action not only curbed the depletion of the ozone layer but also mitigated their impact as potent greenhouse gases, showcasing a powerful global commitment to environmental preservation.

Until now, the Montreal Protocol has avoided an increase in emissions of ozone-depleting substances that nearly equals the increase in global emissions of CO2 over the same period. Without the Protocol, the current effects of global warming would be much more severe.

Since 2019, the Montreal Protocol also tackled the huge climate impact of HFCs through its “Kigali Amendment”, which is jointly implemented by all countries worldwide.

The Meeting of the Parties to the Montreal Protocol (MOP) is currently held once a year. This is usually preceded by an Open-ended Working Group Meeting.

Ongoing challenges and the way forward

Following the adoption of the Kigali Amendment, the meetings now focus on all issues related to implementing HFC reduction measures, continuing challenges to limit ODS emissions and new threats to ozone and climate linked to these substances.

While significant progress has been made globally in reducing HFCs, several challenges remain that require continued attention and international collaboration. Key issues include ensuring the energy efficiency of alternative technologies and addressing illegal production and trade.

- Ensuring energy efficiency and technological transition: One key issue is the impact of the HFC phase-down on the energy efficiency of alternative cooling technologies (namely, the most critical sector using HFCs). The HFC phase-down envisioned under the Kigali Amendment could mitigate global warming by 0.3 to 0.5 degrees. More specifically, improving energy efficiency while transitioning away from highly climate-altering HFCs could prevent another 0.5 degrees of warming.

- Addressing illegal production and trade: The discovery of an illegal production site for chlorofluorocarbons, which should have been phased out by now, started a broader discussion on strengthening the Montreal Protocol’s ability to react to suspected illicit activities and helping countries counter illegal trade more effectively.

The EU’s role

The EU ratified the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol before it entered into force on 1 January 2019. Compliance with the Amendment is fully ensured through the EU's F-gas Regulation.

The EU's leading role and experience in regulating F-gases, including HFCs, provided valuable insights during the negotiation of the Kigali Amendment. As early as 2006, the first EU F-gas Regulation sought to limit HFC emissions – mostly by minimising gas leakage from equipment.

The second EU F-gas Regulation, ratified in 2015, implemented a phase-down of HFCs across our bloc. This anticipated the reduction scheme planned under the Kigali Amendment and showed that significant early reductions are feasible, contributing to discussions on limiting HFCs under the Montreal Protocol. The latest update to EU F-gas rules, F-gas Regulation (EU) 2024/573, prescribes a much faster HFC phase-down and aims to achieve a complete phase-out by 2050 – with a few exceptions for specific sectors.

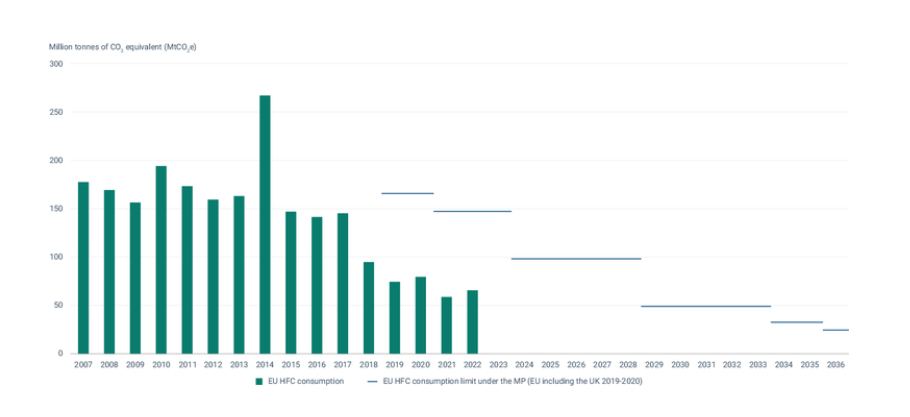

Since HFC reduction obligations under the Kigali Amendment started to apply in 2019, the EU has always remained well below its yearly target – e.g., 55% below in 2022.

The graph depicts the European Union's (EU) progress towards reducing hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) consumption under the Montreal Protocol. The y-axis represents the million tonnes of CO2 equivalent (MtCO2e) consumed, ranging from 0 to 300 MtCO2e, and the x-axis covers the years from 2007 to 2036.

Green bars show the actual HFC consumption by the EU from 2007 to 2022, indicating a peak around 2014, followed by a significant decline. Horizontal blue lines from 2019 onwards represent the EU's HFC consumption limits under the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol. The graph illustrates the EU's progress in reducing HFC consumption, aligning with its international obligations, with a noticeable decline towards near-complete phase-out by 2036.

What is the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol?

In order to address the rapid growth of HFC emissions and limit their climate impact, the Parties to the Montreal Protocol decided to include them as a globally controlled substance under the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol in 2016. This represented a significant step forward in global climate action.

The Kigali Amendment entails a gradual reduction of global HFC production and consumption over the next 30 years, avoiding more than total 80% HFC use. According to estimates, this could prevent a 0.3 to 0.5°C increase in global surface temperature over this century.

Internationally, HFC consumption is regulated through the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol, which came into force in 2019. This amendment commits developed and developing countries to reduce HFC consumption, following progressively declining targets.

Developed countries started with a first reduction step in 2019 and will complete their phase-out by 2036. Developing countries will have to follow a less strict timeline, with most of these countries starting to reduce in 2024 and completing their phase-out by 2045.

By linking the country's mandatory reduction obligations to the climate impacts of the HFCs used, the Kigali Amendment promotes the use of HFCs with lower global warming potentials and, in particular, favours gases that have very low or no global warming potential, such as propane or ammonia.

The Kigali Amendment connects a country's required reduction obligations to the climate effects of the utilised HFCs. This promotes the usage of HFCs with lower global warming potentials – specifically those with very low or no global warming potential, such as propane or ammonia.

How does the global phase-down of HFCs look like?

While the EU leads in reducing HFCs, international cooperation remains key to ensuring global success in addressing climate change.

After adopting the Montreal Protocol in 1988, ozone-depleting substances were regulated and phased out globally. This led to an increased use of fluorinated gases (F-gases) as a standard replacement due to their minimal impact on the ozone layer.

In the past, hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), the most common F-gases used as refrigerants, were the fastest-growing greenhouse gas emission category worldwide, given that they replaced ozone-depleting substances in almost all products and sectors where those were used.

Related links

Why the ozone layer matters and what we’re doing to protect it.