What are fluorinated greenhouse gases?

Fluorinated greenhouse gases (F-gases) highly contribute to global warming. Their warming impact is often thousands of times higher than that of carbon dioxide (CO2). Initially introduced to replace ozone-depleting substances (ODS), F-gases were found to trap heat from the sun and thus make the planet warm up faster.

F-gases are human-made. They include hydrofluorocarbons, perfluorocarbons, sulphur hexafluoride and other fluorinated compounds. Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) represent around 90% of all F-gases. Although you may not know about these substances, you get into contact with them in one form or another each day.

Where are F-gases commonly used in daily life?

F-gases are used in common products, equipment and processes such as refrigeration, air conditioning, heat pumps, insulation, fire protection, power lines, and aerosol propellants as well as in industrial processes. While F-gases are useful in these applications, their negative impact on our climate requires improved regulation and efforts to promote more sustainable alternatives, like ammonia propane or CO2.

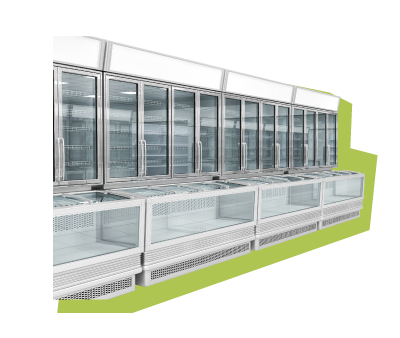

Refrigeration

Refrigeration Heat pumps

Heat pumps Air conditioners

Air conditioners Electric power transmission

Electric power transmission Aerosol spray

Aerosol spray Insulation foams

Insulation foams Electronics

Electronics Industrial manufacturing processes

Industrial manufacturing processes

How do F-gases contribute to climate change?

F-gases contribute to climate change primarily by trapping heat in the Earth's atmosphere. When released, they absorb and hold infrared radiation, preventing it from escaping into space. This trapped heat warms the Earth's surface, creating a phenomenon known as the greenhouse effect, which is the primary cause of climate change.

Some F-gases can persist in the atmosphere for a long time, ranging from several years to even centuries, and therefore contribute to the greenhouse effect over an extended period. Even in smaller quantities, F-gases can have a significant warming impact, whose consequences include altered weather patterns, rising sea levels, and disruptions to ecosystems worldwide.

Measuring the climate impact of F-gases

The climate impact of greenhouse gases can be determined by assessing their Global Warming Potential (GWP), which measures their impact relative to one tonne of carbon dioxide (CO2) over a certain period (usually 100 years). The higher the GWP, the worse it is for the climate.

More specifically, the GWP quantifies how much heat a gas can trap in the atmosphere compared to carbon dioxide (CO2), which is used as the baseline with a GWP of 1. For example, SF6 has a GWP of around 24,300 over 100 years, meaning it is 24,300 times more effective at trapping heat in the atmosphere compared to CO2 during that period. This makes SF6 the greenhouse gas with the worst climate impact.

Each F-gas or mixture of F-gases impacts global warming to a different degree. It is preferable to use F-gases with a low GWP or avoid F-gases altogether, if feasible.

Infographic displaying the Global Warming Potential of common fluorinated greenhouse gases over a 100-year period. Various sizes of blue circles represent the potency of each gas. The gases listed from smallest to largest impact are HFC-1234yf, HFC-32, HFC-134a, HFC-125, PFC-116, HFC-23, and SF6, with GWP values ranging from 0.501 to 24,300. The bottom of the infographic provides alternatives to F-gases like Carbon dioxide with a GWP of 1, Propane with 0.02, and Ammonia with 0. The background is white with blue and green text.

When do emissions of F-gases occur?

Emissions can occur when F-gases are produced, transported, stored, or filled into products and equipment or if they leak during their lifetime or disposal. When contained in products such as aerosol sprays and solvents, for example, F-gases are emitted outright into the atmosphere. It is a fundamental principle in the new F-gas Regulation that everyone must prevent these emissions if possible.

How have emissions of F-gases developed in recent decades?

F-gas emissions, particularly from hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), increased significantly from 1990 due to their widespread use as substitutes for ozone-depleting substances (ODS). Emissions of F-gases in the EU nearly doubled between 1990 and 2014, in contrast to the declining trend observed in emissions of other greenhouse gases during the same period. However, F-gas emissions in the EU have been consistently decreasing each year since 2015, thanks to the implementation of the 2014 F-gas Regulation.

What does the EU do to tackle emissions of F-gases?

Since 2015, the EU has been very efficient in reducing F-gas emissions. Without the 2014 F-gas Regulation, the high level of emissions of HFCs and other F-gases would have remained high.

The 2014 F-gas Regulation introduced a quota system to phase down the most common F-gases, hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs)—with success! In 2024, only one-third of the 2015 amount of HFCs will be placed on the EU market. In addition to this quota system, the EU has implemented complementary measures to lower the leakage of F-gases, encourage the switch to climate-friendly alternative substances, and stimulate innovation and the development of green technologies.

With the rules established by the new F-gas Regulation, HFCs sold on the EU market should be zero by 2050. This goal serves the EU's objective of achieving climate neutrality by that year.

We are also committed to a global agreement to reduce HFC consumption and production, the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol. Notably, in 2022, the EU stayed 55% below its limit specified in the agreement.

Related links

For the past decade, the European Union has been leading the charge against climate change through a landmark law known as the Regulation on Fluorinated Greenhouse Gases (EU) 517/2014.